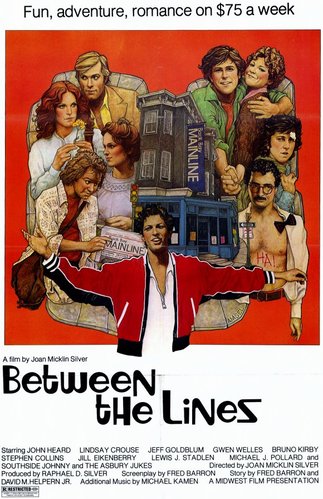

Joan Micklin Silver, 1975

Joan Micklin Silver, 1975

Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors and the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema is the first ever examination of the professional experiences and creative output of women directors during a unique moment in history when the social justice movements that defined the 1960s and 1970s challenged the enduring culture of sexism and racism in the U.S. film industry. The 1970s was a crucial decade for women directors working in Hollywood. The influence of the feminist movement, in particular the political action spearheaded by the Women’s Committees of Hollywood’s most prominent guilds—the Directors Guild of America, the Screen Actors Guild, and the Writers Guild of America —led to the increase of women directors making feature films for the first time in forty years.

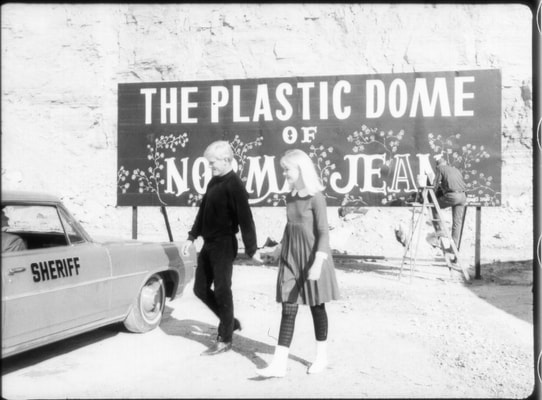

Juleen Compton, 1966

Juleen Compton, 1966

From the mid-1930s till the mid-1960s, only two women had careers as directors in Hollywood: Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino; between 1961 and 1966, two New York-based women were directing independent feature films outside of Hollywood: Shirley Clarke and Juleen Compton.

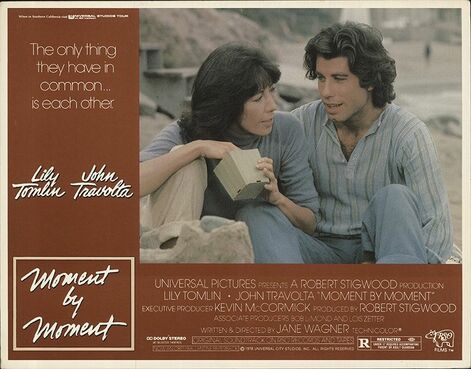

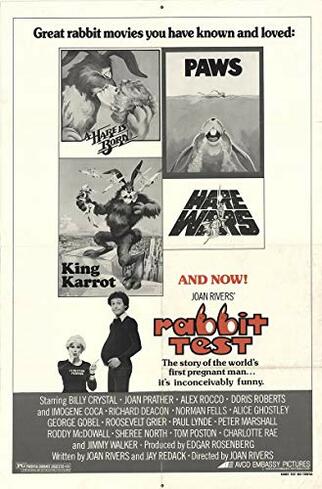

Drawing on oral histories conducted by the author, Maya Montañez Smukler reveals that between 1966 and 1980 there were an estimated sixteen women making independent and studio films: Penny Allen, Karen Arthur, Anne Bancroft, Joan Darling, Lee Grant, Barbara Loden, Elaine May, Barbara Peeters, Joan Rivers, Stephanie Rothman, Beverly Sebastian, Joan Micklin Silver, Joan Tewkesbury, Jane Wagner, Nancy Walker, and Claudia Weill.

Drawing on oral histories conducted by the author, Maya Montañez Smukler reveals that between 1966 and 1980 there were an estimated sixteen women making independent and studio films: Penny Allen, Karen Arthur, Anne Bancroft, Joan Darling, Lee Grant, Barbara Loden, Elaine May, Barbara Peeters, Joan Rivers, Stephanie Rothman, Beverly Sebastian, Joan Micklin Silver, Joan Tewkesbury, Jane Wagner, Nancy Walker, and Claudia Weill.

Jane Wagner, 1977

Jane Wagner, 1977

Hollywood During the 1970s:

The women’s movement had begun to raise Hollywood’s consciousness early in the 1970s. On screen the movement and its objective of female autonomy were represented in several kinds of movies, including large-budget studio films, always directed by men, such as Klute (1971, Warner Bros., Alan Pakula), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974, Warner Bros., Martin Scorsese), and An Unmarried Woman (1978, 20th Century Fox, Paul Mazursky). Off screen, myriad female industry employees began organizing feminist reform efforts. Women in Film was established in 1973 as a networking association created by accomplished women in the industry. In 1974, the American Film Institute founded the Directing Workshop for Women, a program that trained women to become film and television directors. Between 1974 and 1976 both the Writers Guild and the Screen Actors Guild established their own Women’s Committees that advocated job equity for their female constituencies. In 1979, the female members of the Directors Guild formed its Women’s Committee and began calling out studios, networks, and production companies that did not hire women directors, efforts which, in 1983, materialized into the first ever anti-discrimination lawsuit filed by a guild against major film studios: Directors Guild of America, Inc. v. Warner Brothers, Inc. and Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

The women’s movement had begun to raise Hollywood’s consciousness early in the 1970s. On screen the movement and its objective of female autonomy were represented in several kinds of movies, including large-budget studio films, always directed by men, such as Klute (1971, Warner Bros., Alan Pakula), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974, Warner Bros., Martin Scorsese), and An Unmarried Woman (1978, 20th Century Fox, Paul Mazursky). Off screen, myriad female industry employees began organizing feminist reform efforts. Women in Film was established in 1973 as a networking association created by accomplished women in the industry. In 1974, the American Film Institute founded the Directing Workshop for Women, a program that trained women to become film and television directors. Between 1974 and 1976 both the Writers Guild and the Screen Actors Guild established their own Women’s Committees that advocated job equity for their female constituencies. In 1979, the female members of the Directors Guild formed its Women’s Committee and began calling out studios, networks, and production companies that did not hire women directors, efforts which, in 1983, materialized into the first ever anti-discrimination lawsuit filed by a guild against major film studios: Directors Guild of America, Inc. v. Warner Brothers, Inc. and Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc.

Joan Rivers, 1978

Joan Rivers, 1978

Throughout this era feminist reform efforts supported a noticeable rise in the numbers of women directors, yet at the same time the institutionalized sexism of Hollywood continued to create obstacles to closing the gender gap. At the end of the decade the Women’s Committee of the Directors Guild calculated the following statistics: between 1949 and July 1979, 7,332 feature films had been released by major distribution companies. Of these, 7 women directed 14, or 0.19 percent, of those films. Yet the very existence of sixteen women feature film directors working at different times throughout the 1970s meant some were able to break through the barriers to advancement. How they were able to do that is Liberating Hollywood’s central question.

In 2010, Kathryn Bigelow was the first woman, in 82 years of Oscar history, to win an Academy Award for Best Director. This historic moment, and the eight decades it took, underlines how the struggle for parity amongst women directors persists to this day. According to Martha Lauzen’s 2017 annual report, “The Celluloid Ceiling,” the percentage of women directing the top 250 films in the United States has hovered between 7-11 percent for close to twenty years. Women directing independent feature films have done somewhat better, but their numbers are low in comparison to their male peers: between 2011-2015, women directed 18 percent of the narrative features showing at the 23 most prominent film festivals in the United States. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union requested state and federal officials investigate the discrimination of women directors. To date, these claims remain under investigation by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 2017 the #MeToo movement began to sweep Hollywood when massive allegations of sexual harassment against men of power—studio executives, writers, directors, performers—were made by hundreds of women, and some men.

Against this contemporary landscape, Liberating Hollywood provides an historical context in which to understand the continued fight for gender equality in the media industry, today.

Against this contemporary landscape, Liberating Hollywood provides an historical context in which to understand the continued fight for gender equality in the media industry, today.